Why you're not gaining muscle, and what to do about it

I'm trying to use clickbait to make you read about the driest article ever in hypertrophy literature

Top of the morning, sapien. Welcome to Common Sense Medicine, where I try and keep you up to date on the latest and greatest in longevity science.

When I decided to start hypertrophy training, I injured myself on the first day. For all that I talk about injury prevention, I know that I can’t stop it completely. I had wanted to start a new program, and I had started to get ready for the first set of the weighted tricep dips which I was going to do. I felt a quick crick in my back and I knew where it was coming from—my rhomboids always gave me trouble, and now the lower leg mobility I was doing didn’t mean sh** because my upper back had been injured.

So now I have an upper back injury—luckily, it’s mild but it showed me the warning signs of being off your game when it comes to mobility and strength. Don’t try and do any funny business when lifting weights and also don’t go above your means. I’m planning on taking some time next week to discussing my rehab protocol for when I feel pain, so definitely be on the lookout for that in the next few weeks.

Also, happy new year! Like I mentioned, it’s just another day, but that doesn’t stop people from crowding the gym. I’m focused on the 12 weeks which I have until March and probably just focused on my 3 goals for the quarter. 12 weeks, 3 goals. Let’s get it. Okay, enough of the motivational talk—let’s get back to our regularly scheduled science-based programming.

Other items on the differential:

Hypertrophy progress for week of 12/23 and analysis on my crippling addiction to Kirkland Signature protein bars

Apparently my Apple Watch strap is secreting a lot of PFAS (forever chemicals) which are leaching their way into my skin, with extended periods of contact. I’m exercising daily, so my Apple Watch is kind of an essential wearable for me to calculate how much I’m burning in terms of my calorie expenditure. Definitely going to dive deeper into this article in one of the next few issues.

Biological age isn’t a great predictor of how long you’ll actually live. Also, people don’t really agree on what defines “aging” as a disease. But that doesn’t stop people from trying to quantify general health in any way possible. I read this interesting article about an algorithm called FaceAge, which tries to calculate signs of aging in the face recently. It was able to correctly predict survival (using hazard ratios) in a cohort of 6K+ cancer patients (study here) after training on a dataset of 51K+ patients.

THE WEEKLY DOSE

What does it take to grow a muscle?

It’s pretty obvious why I’m interested in the topic of building muscle—I’m pretty motivated in figuring out how to put on lean muscle mass, and it’s protective against factors like aging and chronic disease. I was going through a powerlifting cycle for my last routine and now I’m working through a hypertrophy cycle and gaining weight (see below for progress). In this vein, I got curious to know which method (high-rep, lower weight, or lower-rep, high weight) is actually helpful in building muscle.

So, while reading different sources, I found a publication by Brad Schoenfeld which explored this question, in two ways—(1) defining the physiology of muscle hypertrophy and (2) deciding what the optimal protocol is for strength training.1 This was a literature review, essentially, with a focused question which is why I liked and read it (all 16 pages of it!). This article was pretty dry but honestly, pretty informative and showed me some things that I didn’t know already.

Let’s dive into the cellular mechanisms of hypertrophy

I didn’t realize that for the first few months of strength training, you don’t really see hypertrophy. Since I started weight training in earnest in April, I guess I’m still waiting for my gains. Hypertrophy, when contrasted with hyperplasia, is growth of the myofibers, specifically the amount of actin and myosin, and the total number of sarcomeres in parallel. When cells get injured, they have to recruit satellite cells to repair them (after a heavy workout, for example), which then increase the mRNA production, protein synthesis, and donate myonuclei when trying to repair and build stronger cells.

There are various cellular mechanisms of hypertrophic growth: mammalian target of rapamycin (Akt/mTOR), Mitogen-Activated Protein-Kinase pathway (MAPK), and calcium dependent pathways (Ca2+ dependent pathways). Out of these, MAPK has been shown (through a signaling molecule called JNK) to be associated with eccentric based exercises, and Ca2+ pathways depend on a molecule called Calcineurin to signal muscle hypertrophy.

In terms of hormones, IGF-1, a peptide hormone, is considered the most important anabolic mammalian hormone, which “kick starts” muscle hypertrophy through an variant of its’ structure (IGF-1Ec) called an isoform. IGF-1Ec is also called mechano growth factor (MGF). However, testosterone also plays a role in hypertrophy, showing increase in satellite cell numbers and also increases the androgen receptors which respond to testosterone, creating a positive feedback cycle.

Zooming out to a macro level, there’s three main drivers of muscle growth

On a macro level, three things cause hypertrophy when you exercise: mechanical tension, muscle damage, and metabolic stress. Mechanical tension works by disturbing muscle integrity, activating Akt/mTOR pathways, and creating passive tension during eccentric movements, but it’s not sufficient for muscle growth alone. Muscle damage ranges from small molecular damage to larger tears, which triggers an inflammatory response which attracts neutrophils, macrophages, and lymphocytes to the damaged area and stimulates satellite cell activity near the myoneural junction which helps mediate muscle growth.

Metabolic stress plays a significant role through the buildup of metabolites like lactate (we’ll talk more about this in a few months with marathon training), hydrogen ions, and phosphate during anaerobic exercise. It also creates cell swelling and an acidic environment which enhances the adaptive response. This mechanism is particularly evident in moderate-intensity bodybuilding training, which emphasizes metabolic stress while maintaining muscle tension.

The six frameworks which matter when actually going to the gym to get jacked

There are six frameworks which you should think about when engineering for hypertrophy while training:

Training Intensity (Load): This is the #1 variable which you should consider when thinking about hypertrophy. High (15+) reps don’t induce as much hypertrophy, unless you’re doing blood flow restriction training inducing metabolic stress. Therefore, focus on doing moderate (6-12) reps or low (1-5) reps. In fact, moderate reps have been shown to have higher levels of anarobic glycolysis, which has been shown to have a significant impact on anabolic processes due to the impact on metabolic stress rather than only muscle tension. Additionally, the longer rep ranges can also stimulate slow-twitch muscle fibers (2-for-1 deal!).

Volume: How many sets you’re doing of an exercise. I already do 3-4 in my workouts, this paper basically says the same thing. He also says that you have to limit workouts to an hour to maximize hypertrophy and try to program body parts on specific days to ensure that you are able to fatigue the muscles enough to implement the hypertrophy response. Volumes should also progressively increase over time leading up to a ‘peak’ phase, after which there should be a taper or cessation from exercise so that you can recover and get back to your baseline state rather than being overtrained.

Exercise selection: Both multi-joint and single-joint exercises are valuable and different angles and movements target various muscle regions. Honestly pretty self-evident, but this can be seen when you have to target different parts when you’re not training each muscle. For example, I wasn’t really focused on upper back development in a prior program, and in this one, I have to be more focused on it. It’s just like a diet—you gotta have a varied one if you’re going to be fit. Furthermore, multi-joint exercises trigger greater hormonal responses. This is why you’re always hearing that compound exercises (i.e., squat, bench, deadlift, the holy trinity) perform better than machines. Finally, this was an interesting tidbit which I took away as well—unstable surfaces generally reduce force output and aren't recommended (except for core training)

Rest periods: Moderate rest periods (60-90 seconds) appear optimal. Short rests (≤30 seconds) impair strength too much. Long rests (≥3 minutes) reduce metabolic stress. The body adapts to shorter rest periods over time. This is something that I’m definitely trying to improve—when I have a hard set, I have to really focus and say that I’m trying this again after a minute or two. The reason for the long rests causing less muscle hypertrophy is due to the lack of metabolic stress—lifters with moderate rest achieved a higher mean 1RM than those who didn’t in the literature.

Training to failure: May activate more muscle fibers and increase metabolic stress. Should be used periodically to avoid overtraining, and not every set needs to reach failure. Consistently training to failure caused a reduction in IGF-1 concentrations and blunting of resting testosterone in one 16-week study, suggesting that subjects were overtrained.

Repetition Speed: When lifting the weight, you should target a fast to moderate speed (1-3 seconds). When lowering the weight, target a slightly slower speed (2-4 seconds). Very slow training, or deliberately causing a slow movement, is suboptimal for muscle growth. The eccentric phase is more important than the concentric phase for muscle growth; this is something I didn’t know about before reading this paper.

So what am I changing about my routine?

Practical takeaways from the paper is that I’m doing a pretty good job on the front of programming. I think the more important outcome which I’m targeting is focusing on what I’m actually doing at the gym, starting with the repetition speed and training to failure. I think the first three frameworks I have covered with my current routine, and there isn’t much that I can do to optimize it.

For rest periods, I think I can use my Apple Watch to monitor the rest periods so I’m focused on only using 60-90 seconds, and keeping an eye on the time so I’m not risking overtraining by going too long. Also, when I’m actually doing the reps, I can focus on the eccentric more than the concentric movement, and use the last set as a “training to failure” rep every other week so that I’m occasionally really testing my limits. This article also showed me that I don’t need to deliberately slow down my reps, but rather the eccentric movement just has to be a little bit longer than the concentric movement, and just focus on doing it for 3 seconds rather than a quick lift and let go.

THE PRESCRIPTION

Q1 2025: Hypertrophy Cycle Progress

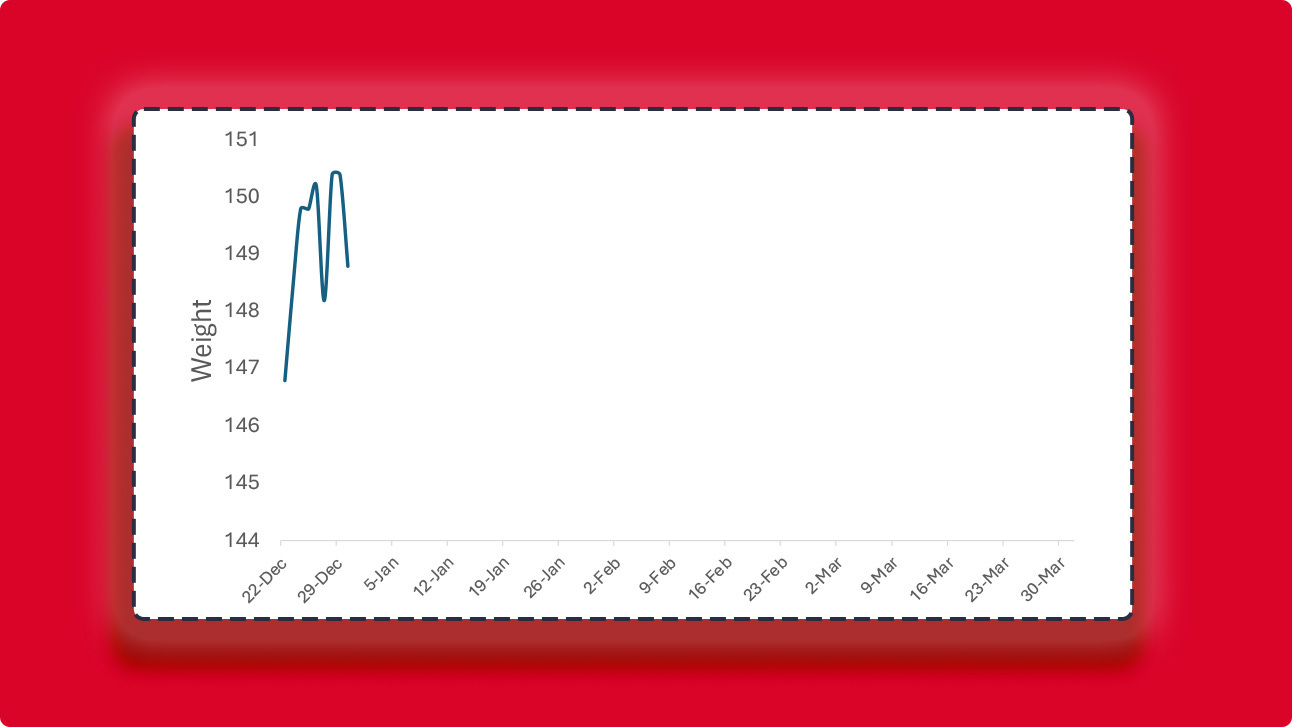

The upshot: Gaining weight slowly but steadily. Keep on keepin’ on.

More information: The analysis here isn’t too broad but on the whole, we’re seeing a modest increase in weight. I think that 3000-3500 calories is a great sweet spot for me. The problem is I have a crippling addiction to Kirkland Signature Chewy Protein Bars which spike my carb intake sky-high. I housed 7 of these bad boys in a day, 1,000+ calories of straight protein bar (1,330 to be exact).

I say this not to shame myself, but to say that even though I’m getting the “right answer” by showing that my weight is going up, sometimes it’s not in the best way. Will continue to improve and report back on how nutrition is going. I’m going to try and focus on a similar diet which I had in the summer of 2024, where I focused on preparing meals beforehand and focused on a base of fat / protein and added carbs more sparingly.

REMEMBER, IT’S JUST COMMON SENSE.

Thanks so much for reading! Let me know what you thought by replying to this email.

See you next week,

Shree (@shree_nadkarni)

The information provided here is not medical advice. This does not constitute a doctor patient relationship and this content is intended for entertainment, informational, and educational purposes only. Always consult with a doctor before starting new supplementation protocols.

Schoenfeld BJ. The Mechanisms of Muscle Hypertrophy and Their Application to Resistance Training. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2010;24(10):2857. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e840f3