The next frontier of Alzheimer Disease Screening

While we can't predict whether you'll get Alzheimer's, we can certainly try

Top of the morning, sapien. Welcome to Common Sense Medicine, where I try and keep you up to date on the latest and greatest in longevity science.

Writing this in a bit of a tight spot in two ways. First, I’m focused on stretching and hip impingement issues. I squat ~1x / week, and I’ve been feeling some pain in the anterior hip while I go down. I’m attacking it with the same routine—heat, foam rolling, and stretching is the goal focusing on the same standards which I wrote about a couple of week ago. I’ll report back on how the hip mobility project is going over time.

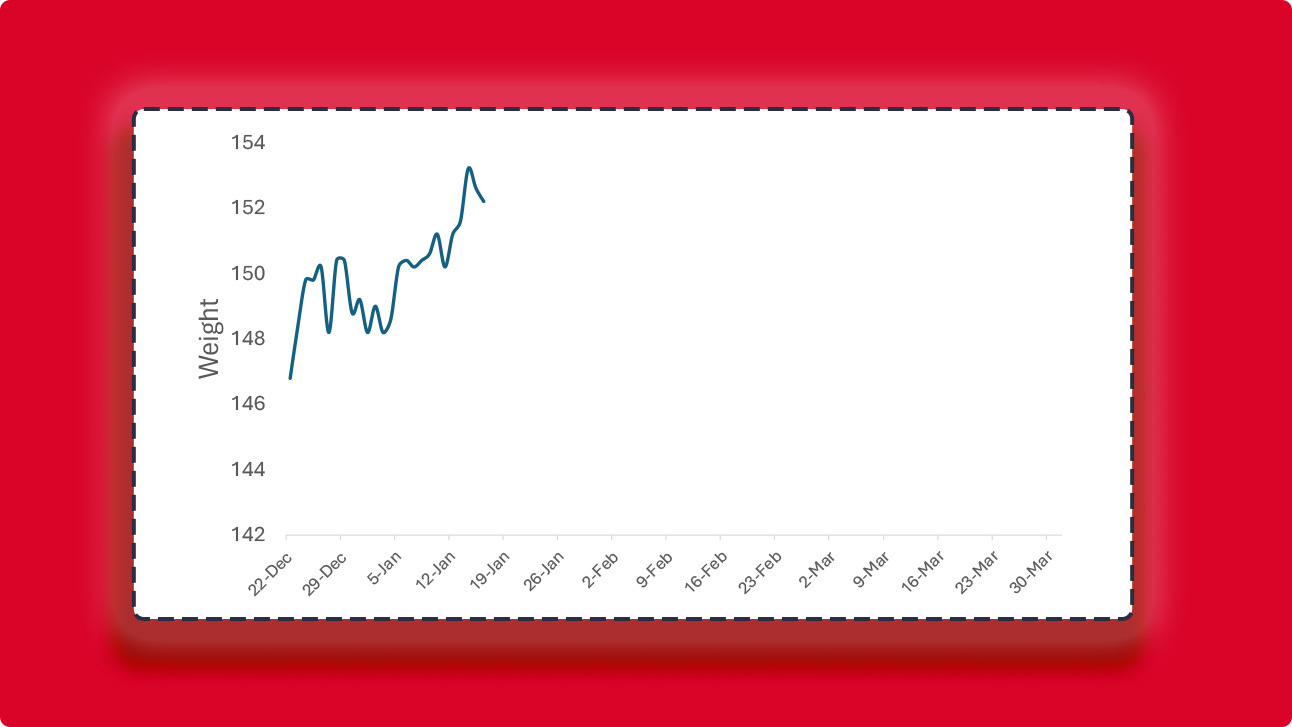

Second, I’m still working on that test prep, so time is a bit tight, but working on getting out an issue a week. Hypertrophy progress is below. It’s a tiring grind, but we’re getting through it. Let’s get down to business.

Other items on the differential:

Try this sleep experiment when you get a chance. I’m going to try it in earnest next week after my test and see if it improves my sleep as measured by the Apple Watch and Oura Ring. It’s an interesting test to try, and it’s an endpoint which I’m curious to learn about. I know that my late-night snacking is probably the worst habit that I have, so I’ll use this excuse to try and kick it.

People are generally aging more gracefully. In all areas of their life, they’re improving their psychology, their locomotion, their vitality, and more. It’s not just men or women who are gaining these trends, but largely constant across genders. I think it’s because of modern medicine that we have this, but also the recognition of “an ounce of prevention is worth more than a pound of cure.” (source)

THE WEEKLY DOSE

The Remembrall is back, y’all

I remember in Harry Potter when Neville Longbottom opened up his gift for Christmas and found a Remembrall. It was kind of a useless gift, because it lit up when someone forgot something, but they couldn’t remember what they’ve forgotten. The reason I included it in today’s issue, however, is because we’re talking about a disease which kind of works like a Remembrall—by the time you can clinically diagnose it, it’s already too late. Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is one of the most insidious causes of neurodegenerative disease, and it’s part of the reason why we can’t achieve longevity escape velocity. It’s also sad but fitting that it causes you to lose your memories, which is exactly what a Remembrall indicates.

Palmqvist et al. had a similar question, albeit more focused on a proof-of-concept study where they were trying to validate that a blood test could tell you whether someone had AD or not.1 Right now, in order to diagnose someone with AD in a laboratory, you need to either get a sample of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) to measure a protein called amyloid-beta or get a brain imaging test called a PET scan. There’s a whole bunch of tests in development right now, but they haven’t been accepted into standard practice. Then you also need to corroborate that with a clinical diagnosis.

Researchers are developing these tests not only to make a whole lotta cash from selling these better, more improved diagnostics, but also to get patients enrolled in trials faster. This has the downstream effect to treat them faster with the two approved anti-amyloid therapies on the market currently.

PrecivityAD is a test which can augment clinical diagnosis of early Alzheimer’s Disease

This study examined a blood test called APS2 (amyloid probability score 2) which combined the ratio of phosphorylated tau 217 (p-tau217) to non-p-tau217 and the ratio of amyloid-beta 42 to amyloid-beta 40 in plasma.

They first recruited 1,213 patients from both primary and secondary care settings in Sweden for this task from 2019 to 2024. Physicians were tasked with deciding whether patients had Alzheimer’s Disease before they saw any biomarker results—they were able to use their clinical examination, cognitive testing, and a CT scan and rated their confidence that a patient had AD from 1 to 10. The study used cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) measurements to measure gold standard of AD diagnosis and their primary outcome was to see whether they could diagnose AD from a blood test. The value which they used as the “gold standard” was the ratio between amyloid-beta 42 to amyloid-beta 40 in CSF which has been FDA-approved as the standard for laboratory diagnosis of AD. If participants couldn’t undergo a lumbar puncture, they were evaluated using PET scans for Amyloid-beta.

The investigators also used both a 1-cutoff (AD / no AD) 2 cutoff-value approach (using 1 upper and 1 lower cutoff value, with the middle region being “intermediate”) based on cerebrospinal fluid (AD / no AD / intermediate). They used a stricter criteria (95% specificity and sensitivity vs. 90%) for 2-cutoff versus 1-cutoff values, respectively. Clinical AD was used as a secondary outcome, which means that the patient had a positive blood test and a positive biomarker for AD. Notably, they could also have signs of another co-morbid disorder (i.e., vascular dementia or Lewy Body disease), but AD was the show which they were concerned with primarily.

The test performed well when compared to the gold standard, and outperformed human physicians

These were the values for the various tests that they ran in the population for single-batch testing, retrospective from Oct 2020 to 2022. They had a different population for prospective testing as a cohort which they were monitoring over time, but they threw that one in the supplementary information for both primary and secondary care. As you can see, there is a clear statistically significant advantage here for using this blood biomarker for diagnosing AD. Dementia specialists were not allowed to see any biomarker data before they made their clinical diagnosis, which is kind of cheating honestly (because which physician makes their diagnosis clinically for something as serious as AD), but it made sense because the developers of this test clearly don’t want to show that their test is inferior to the doctor.

Okay, moving onto the positive predictive value for the tests. Usually, when you’re thinking about a diagnostic test, you want to know whether you actually have the disease if you test positive. This is critical in AD because you don’t want to start someone on (a very expensive) treatment if you can avoid it, and they don’t actually have the disease. As you can see, the PPV is pretty high for both of these populations with the APS2 blood test, comparable to the gold standard and the % p-tau217 test (already shown to have high concordance with the CSF concentration of amyloid-beta 42:40).

While APS2 screens you for when you already have signs of AD, it doesn’t really help with subjective cognitive decline. The PPV / NPV is pretty piss poor if you ask me whether you’re trying to figure out whether you have Alzheimer’s or not when you have “subjective cognitive decline” AKA “we have no idea if you have cognitive impairment”. You can see the confidence intervals get pretty large, and the error bars get all over the place when you’re asking whether you have the disease or not when you’re testing positive. Therefore, I think the innovation in this study largely stems from the fact that (1) the investigators developed a novel blood test and had cutoffs which were comparable to CSF based tests, which are significantly harder to collect, and (2) they validated it in primary care settings, where AD is not usually diagnosed.

Prediction for AD remains shoddy, but screening is an important start

The upshot of this study is that we have new modalities to screen for AD in the primary care setting using a blood test, which gives a reasonable PPV comparable to the lengthy process of getting a PET scan or a CSF collection. This is really helpful to evaluate and stop mild cognitive decline in its’ tracks, because time is of the essence when we’re talking about chronic disease. AD, cancer, and diabetes all are helped if you catch them early and intervene aggressively, which is why you see everyone talk about getting an APOE genetic test or HIIT exercise to prevent the onset of neurodegenerative disease.

I think the most important lesson from this paper broadly is that there should be inexpensive ways to evaluate a large majority of the population for devastating diseases like AD. I think that the development of this test means that the field is moving in the right direction. While it’s not really predictive yet, I think that there’s potential in including something like this in a primary care setting. I think that where it becomes focused on longevity is including this in longitudinal settings and seeing how it performs with people on different lifestyle modalities, and matching it to different phenotypes and genotypes by sequencing people’s genomes. We know that the amyloid hypothesis is under some duress, after there have been faked research papers which cast doubt on a progression of disease based solely on the amount of amyloid that there is in the brain.

However, I think this is an important, incremental state forward. I’m really bullish on the idea that health is based on what you can detect, and that as algorithms get more personalized based on your own genotype, then we’re more likely to figure out who will get diseases and who won’t. Right now, for the diseases which we can’t cure, it’s likely about how early you can catch it. This test doesn’t really catch it early, but it is a promising start for how we can scale diagnosis parameters more widely so that we catch more people in that “early” bucket before they have full blown AD.

THE PRESCRIPTION

Q1 2025: Hypertrophy Cycle Progress

REMEMBER, IT’S JUST COMMON SENSE.

Thanks so much for reading! Let me know what you thought by replying to this email.

See you next week,

Shree (@shree_nadkarni)

The information provided here is not medical advice. This does not constitute a doctor patient relationship and this content is intended for entertainment, informational, and educational purposes only. Always consult with a doctor before starting new supplementation protocols.

Palmqvist, Sebastian, et al. “Blood Biomarkers to Detect Alzheimer Disease in Primary Care and Secondary Care.” JAMA, vol. 332, no. 15, Oct. 2024, pp. 1245–57. Silverchair, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2024.13855.