The influence on sleep, training volume, and recovery in athletes

I became a little too eager with my training, and had to take a step back. A study suggests that modulating training volume could be the cause of the decrease in immune response.

Top of the morning, sapien. Welcome to Common Sense Medicine, where I try and keep you up to date on the latest and greatest in longevity science. In the past week, I’ve had to take a step back from my training volume as I had a case of a respiratory virus. I also recently watched this video by Dr. Vinay Prasad which mentioned the flawed thinking around controlling the spread of flu / rhinovirus.

I think in the past few months, I have been pushing very hard on trying to be consistent, and being very rigid about my routine, but not really listening to my body about taking it slow. I think the goals which I’ve set for myself (gain X lbs. of muscle, X% of body fat) doesn’t acknowledge the fact that there will be times when I need to take steps away from my training.

I still have a lingering cough from the sickness that started in force last Thursday, so what I was planning was to try and start with yoga / cardio, including the eccentric achilles strengthening, on Thursday / Friday to pick back up into activity, and then have a tentative weightlifting session to finish up the week on Saturday.

I guess I have to be more mindful about sleep and recovery going forward to try and prevent sickness, but I just can’t help getting sick at least one point in the year. Reddit has a bunch of information about preventing getting sick but I think doing the basics and sleeping, recovering, and washing hands can help with preventing sickness as much as possible.

THE WEEKLY DOSE

How is sleep related to illness in athletes?

This week’s publication comes to us courtesy of an Australian team from Macquarie University with the clinical question of how sleep, training volume, and illness are related. It’s pretty intuitive that you feel objectively worse when you sleep less, but is there a dose dependent relationship between the two? Fitzgerald et al had that question and wanted to see the correlation in football players (it’s the Bizarro cousin of American football, the superior form of football).1 I think this cohort is a bit more robust than other populations but I thought it could be comparable to a more younger audience (i.e., me) and wanted to see what kinds of sleep regimens they were working with and their incidence of sickness rather than an older cohort.

What did they do?

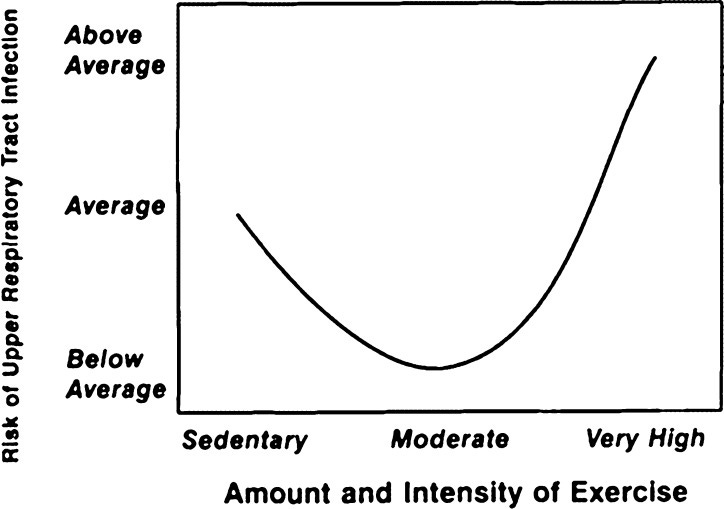

The investigators already knew that there was a relationship between the risk of respiratory tract infection and training load, but didn’t really understand how the addition of sleep could affect that (see Figure 1). For example, say that you have a player who is training pretty hard, but is sleeping properly—do their rates of illness decline? Is it just that the players who are training hard are disrupting their sleep as well? The study was designed to see, over a period of 46 weeks (so they had the whole year to make their recommendations on), to answer the question about the relationship of training load and sleep (independent variables for each subject) on the incidence of illness (dependent variable).2

Figure 13

They took 44 players and examined external workload, internal workload, and sleep parameters. External workload was examined using total distance, high speed distance (>17 km/h), and sprint distance (>23 km/h), each expressed in meters traveled using wearables. Internal load was measured using a RPE (rating of perceived exertion), where players marked how tough the workout was for them (from a 0-10 scale). Qualitative and quantitative sleep parameters were recorded using self-reported metrics — players answered questions on how much they slept last night and how they evaluated their own sleep (on a Likert 5-point scale, where 1 was ‘perfect sleep’ and 5 was ‘hardly slept’).

Illness incidence was calculated as number of illnesses per 1000 running hours as recorded through GPS tracking. Acute (< 7 days prior to illness) and Chronic (< 28 days prior to illness) workloads were calculated.

What did they find?

First, the 44 players who were analyzed had a mean age of 24 years ± 3.4 years, which makes this study a little more applicable to my training. Where it falls short is that they are running significantly more than me, but it is a goof goal to shoot for. Across the 46-week season, they found an incidence rate of illness of 11.9 illnesses per 1000 h of running or 1 illness incidence per 84 hours of running.

When they compared the results across all athletes, they found that while individuals who became ill ran and sprinted less distances in the 7 days prior to when they got sick, this didn’t result in a greater incidence of getting sick. However, poorer sleep quality (especially acute sleep quality) showed a greater chance of getting sick. This even held up when they tried the multivariate regression: when all other variables were accounted for, acute sleep hours (quantity of sleep) was associated with a greater odds for illness in this specific cohort (OR 0.49, p=0.032). Essentially, this means that people who slept more hours were 51% less likely to get sick compared to those who slept fewer hours in the 7 days preceding their illness.

How does this change my view on sleep?

I already knew sleep was important, particularly because everyone had honestly beaten it into my head. Restricting sleep in a 7-day period prior to infection, while keeping training load high, is a recipe for disaster, creating a biological change with increased cytokines and increased inflammatory markers. It’s helpful that I have a tracker, but sometimes my Apple Watch dies, and it’s hard to track my sleep every night.

In this study, the changes between the people who slept more and less was only 27 minutes. This might seem small, but studies on chronic sleep deprivation have shown that you can increase cold susceptibility by 3.9x with only a 2-8% of sleep duration.4 Large training loads still may cause me to have susceptibility to illness, in contrast with this study, because I am still what is classified as a sedentary person—I don’t exercise for a living (unfortunately), but I do think that elite athletes may have some leeway with increasing their training load and not getting sick (partly because what’s considered ‘moderate’ is very subjective).

Furthermore, the sleep hours were also self-reported, so people may have under-reported their hours when they felt worse, but this would have caused a stronger correlation if the objective hours were measured through a wearable like an Apple Watch. Unfortunately, I couldn’t compare my hours of sleep to this study because I wasn’t wearing my Apple Watch in the 7 days preceding my illness, but I think going forward, I’m going to try and wear a wearable to bed (either an Apple Watch or a Oura Ring to try and approximate the time that I’m spending in bed and sleeping). Hopefully, this can help me get back on the bike and gym, and prepare me for a head start for running come January.

REMEMBER, IT’S JUST COMMON SENSE.

Thanks so much for reading! Let me know what you thought by replying to this email.

See you next week,

Shree (@shree_nadkarni)

The information provided here is not medical advice. This does not constitute a doctor patient relationship and this content is intended for entertainment, informational, and educational purposes only. Always consult with a doctor before starting new supplementation protocols.

Fitzgerald D, Beckmans C, Joyce D, Mills K. The influence of sleep and training load on illness in nationally competitive male Australian Football athletes: A cohort study over one season. J Sci Med Sport. 2019;22(2):130-134. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2018.06.011

Illness was defined using the IOC definition of any “new or recurring symptomatic sickness or disease incurred during [the AFL preseason and competition season that received medical attention, regardless of the consequences with respect to absence from competition and/or training.” Illness was recorded as a dichotomous variable (either ‘ill’ or ‘not ill’) by medical staff

Chamorro-Viña C, Fernandez-del-Valle M, Tacón AM. Excessive Exercise and Immunity: The J-Shaped Curve. The Active Female. Published online August 29, 2013:357. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-8884-2_24

Cohen S, Doyle WJ, Alper CM, Janicki-Deverts D, Turner RB. Sleep Habits and Susceptibility to the Common Cold. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2009;169(1):62-67. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2008.505