Hydrate or Diedrate

When should you actually replace electrolytes? When am I going to?

Top of the morning, sapien. Welcome to Common Sense Medicine, where I try and keep you up to date on the latest and greatest in longevity science.

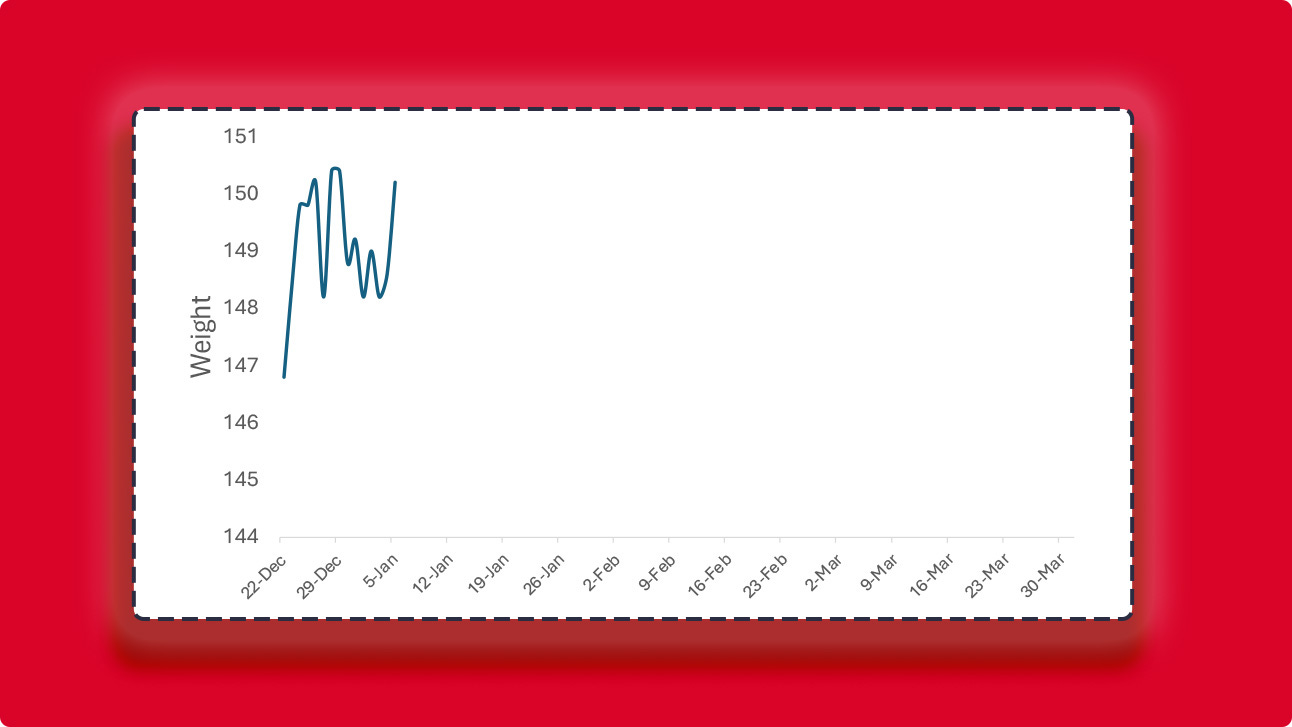

Although hypertrophy progress is chugging along, I’m preparing for a big exam for my residency and need to be heads-down to focus. This might mean that the graph doesn’t have some “analysis” and also that these issues have less of an “intro.” Don’t worry though, I have a plan to keep myself accountable. I’m also still writing furiously to get to my goal of continuing this weekly newsletter.

Other items on the differential:

I’ve entered this competition from influencer Jeff Nippard’s app called MacroFactor. It’s a cool competition which focuses on bettering yourself in 2025 in the next 100 days, and the grand prize winner gets $50,000. Entries end on January 10. Come join and do it with me!

A lot of this newsletter is about self-improvement and taking things as they come. I recently watched this three-part docu-series about “How to become more attractive, scientifically” and I thought it was a fun watch about how sometimes ‘beauty is not in the eye of the beholder.’ Sort of like how longevity means different things if you ask different people.

I recently used my FSA to grab a new pair of glasses right before New Years. If your FSA has a grace period, here’s a quick reminder to use it to get something before it expires! You can use your FSA funds on Amazon as well—it’s a cheap way to get some sunscreen at a discount.

THE WEEKLY DOSE

Is electrolyte supplementation needed after exercise?

Okay, so this question is a HUGE one to answer in one newsletter, but it’s not really taking one study and analyzing it, but rather combinations of multiple studies into practical takeaways for the weekend warrior. There are a few randomized controlled trials which I wanted to dive into, and they all focus on endurance athletes. As I’m focused on doing the half marathon during the second half of the year (I’m still figuring out which one I want to do), I heard that for these longer races you need to have a ‘fueling strategy.’ One part of that is carbohydrates which are fast-digesting so your body can digest them faster but the other part is hydration.

In my review of Ready to Run, I noted that one of the standards which I agreed with was drinking water spiked with electrolytes. I wasn’t sure whether that was totally accurate for every scenario, so I decided to dive deeper. I took a look at three studies which I found about salt supplementation in endurance athletes (triathletes, cyclists, and runners) and also one study about the total volume of water consumed on effects of weight loss and nephrolithiasis (kidney stones).

Ironman times were faster when consuming more salt

In 2016, Coso et al. had the question whether oral salt supplementation to improve performance during a half-Ironman.1 In endurance training, the main physiological benefits of using electrolytes is to preserve serum electrolyte concentrations when they are reduced by sweating. Their main observation was that there was no consistency between lab experiments where they matched fluid intake to sweat loss and field experiments. In the lab, endurance athletes improved their performance but in the field, they didn’t see this improvement. Also, the field experiments didn’t control for various confounders (i.e., cardiorespiratory fitness, training status, and carbohydrate intake)

The authors used this inspiration to measure salt intake before a race and see if performance was improved. All patients were male and they were matched by age, training status, and best half-Ironman times. They received set amounts of sodium (113 mmol), chloride (112 mmol), potassium (19.3 mmol), and magnesium (5.4 mmol) which they were told to consume at transition points throughout the race. They found that controlling for all of the confounders which they evaluated, the mean time taken to complete the half-Ironman triathlon was longer for the placebo group (who just had isocaloric tablets of cellulose instead of the electrolytes) than the treatment group (333 vs. 307 minutes, respectively, p=0.04). The placebo group didn’t have statistically significant decreases in body mass (p=0.09) and they consumed a similar amount of calories during the race.

Due to the osmotic gradient that salt causes (more particles in blood), electrolyte consuming athletes consumed more water during the race, about half a liter (26% more than the placebo, p=0.05). The authors posited that this may have been the cause of the increased performance, but no conclusions can be drawn from just correlations.

No difference in cyclists or runners when consuming more salt

The second study which I looked at was a 2015 double-blind, randomized trial of 11 endurance athletes.2 They tested the effect of high-dose sodium tablets (900 mg/h) in athletes undergoing a 2-hour workout at 60% max heart rate. They looked at multiple secondary metrics—thermoregulation, sweat rate, perceived heat stress, or skin temperatures and the secondary outcomes of cardiovascular drift, ratings of perceived exertion (RPE), and time-to-exhaustion. Lots of metrics. The upshot was that there was no significant differences across all of these metrics, which shows that it is fickle in terms of how these metrics are measured. More specifically, the investigators mentioned that their study might have been underpowered in order to notice a slim effect.

I think that the diet which the participants consumed (which were controlled using a food diary, a notoriously unreliable method of measuring what people consume) might have had a larger effect on the performance metrics, along with the sleep that they had before the test took place. I think with electrolytes, we’re all just chasing marketing when you could be better off (if you are running very very hard, like 2 hours+) in just replacing your fluid intake by measuring your weight after and seeing how much you need to drink post workout rather than shell out an arm and a leg for branded electrolyte tablets which are just flavored salt water, at the end of the day. It’s okay to drink them, and they might help your performance through the osmotic gradient, but there are specific people it will help and the effect, from these two studies, is very miniscule.

The third study was a randomized, crossover study which assessed differences in performance of nine well-trained cyclists (both male and female) in cool weather in New Zealand (side note: I’d love to be a participant in this study).3 They consumed water as needed, like in the other studies, and were given the same dietary meals pre- and post-trial. They were given 233 mg sodium chloride tablets or placebo tablets and were told to consume 3 tablets per hour, equating to 700 mg NaCl. They found, like the Ironman study, that the salt group consumed more water but there was no difference in performance this time (172 minutes vs. 171 minutes for salt vs. placebo, p=0.46)

Water helps a bit with weight loss and kidney stones

Okay, so we’re kind of seeing a pattern here—salt causes more thirst, which causes you to drink more water. But is drinking more water even good for you? A meta-analysis by Hakam et al. collated data from 18 RCTs which measured water intake from various ranges (4 days to 5 years) to answer this question, across various dependent variables: weight loss, fasting blood glucose level, headache, urinary tract infection, and nephrolithiasis (kidney stones).4 They found that adults with obesity found greater weight loss than control groups in 3 of the 18 trials considered (not really a ringing endorsement here). Only 4 of the trials even considered weight loss as a primary outcome. They also found significantly decreased rates of nephrolithiasis in the 2 studies which looked at this primary outcome, although that’s not really performance-focused, per se.

Practical takeaways

I saw this blog post from TrainingPeaks which breaks it down quite succintly—try to test your pre- and post-run weight to make sure that you are figuring out how much you’re actually losing. Let’s use the example in the post. If I’m 150 lbs. (I’m actually around this weight) and the base hydration rate should be ~1 oz/kg of water in athletes. This comes out to 68 oz. of water per day. I’ve seen a number as high as 131 oz though in the adequate intake (AI) for dietary reference intervals for males 19-30.

Okay, now moving onto the workout. I drink 12 oz. during my workout. If I lose 0.5 lbs. after my workout, I should be replacing 16 oz. per pound lost. So the calculation then becomes:

So, they basically say to drink 1 cup/hour that you’re awake and you’ll probably be okay, depending on how much you work out. This is assuming that you have a diet high in fruits and veggies, and that you’re not losing more water because you’ve weighed yourself before your workout. I think for me, another more practical (and even more simple) test is to look at the pee color and then drink water. If it’s pale, then you’re probably hydrated enough.

This might have been kind of a silly post—all of these words to say that electrolytes are probably bunch of baloney, but I think it served two purposes—(1) electrolytes are useful in making you consume more water (which you probably need during a race), and (2) hydration during daily living is important, to the tune of ~1 cup/hour.

Practically, this means that I should be hydrating about 1 cup/hour (I usually forget to drink water) and that if I’m going to use electrolytes, I’d probably be better using the table salt than any other electrolyte tablets. They taste a lot better though, so maybe I’ll buy them to incentivize me to drink more water.

THE PRESCRIPTION

Q1 2025: Hypertrophy Cycle Progress

REMEMBER, IT’S JUST COMMON SENSE.

Thanks so much for reading! Let me know what you thought by replying to this email.

See you next week,

Shree (@shree_nadkarni)

The information provided here is not medical advice. This does not constitute a doctor patient relationship and this content is intended for entertainment, informational, and educational purposes only. Always consult with a doctor before starting new supplementation protocols.

Del Coso J, González-Millán C, Salinero JJ, et al. Effects of oral salt supplementation on physical performance during a half-ironman: A randomized controlled trial. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports. 2016;26(2):156-164. doi:10.1111/sms.12427

Earhart EL, Weiss EP, Rahman R, Kelly PV. Effects of Oral Sodium Supplementation on Indices of Thermoregulation in Trained, Endurance Athletes. J Sports Sci Med. 2015;14(1):172-178.

Cosgrove SD, Black KE. Sodium supplementation has no effect on endurance performance during a cycling time-trial in cool conditions: a randomised cross-over trial. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2013;10:30. doi:10.1186/1550-2783-10-30

Hakam N, Guzman Fuentes JL, Nabavizadeh B, et al. Outcomes in Randomized Clinical Trials Testing Changes in Daily Water Intake: A Systematic Review. JAMA Network Open. 2024;7(11):e2447621. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.47621