Are South Asians weak?

Computer says: Yes

Top of the morning, sapien. Welcome to Common Sense Medicine, where I try and keep you up to date on the latest and greatest in longevity science.

Currently, I’m in India and I’ve only exercised 2/5 days this week. This lapse caused me to reflect on how traveling is disruptive to multiple parts of your health:

Sleep - when you’re traveling, you’re in another part of the world and your bed isn’t the one you normally sleep in. This week, it’s a relative’s couch or floor since space is tight. You also need to wrench your schedule back and forth until it lands on the right time(s) (check out my jet lag protocol)

Exercise - I don’t have a gym to go to, nor can I make time to go to the gym because there’s a language barrier. This may be an excuse, but since I’m going from one place to another, the agenda doesn’t really have time for exercise. On the two days I exercised, I did push ups and squats in the bathroom before we left to go to the main town.

Diet - This is one of the hardest parts. In India, it’s carb / sugar central — everything from the milk to the yogurt (dahi) has sugar in it like you wouldn’t believe. I learned that their fat content in cow milk starts at 3.2% (for context, whole milk is 3% in the US) and goes up to 9% (!). Plus the state of India which I’m in is pretty vegetarian, so protein is harder to find (not impossible, but it’s been a grind supplementing with protein powders and peanut butter when I get the chance).

More alarmingly, however, India’s air quality is abysmal. It’s hard to get a breath in without it smelling like haze or smoke, especially if you’re visiting a city (which I was). It doesn’t matter even if you’re on the outskirts, the air quality sucks. Even Bryan Johnson, the godfather of anti-aging, had to leave a podcast recording in India because of its’ air quality.

Again, moderation in everything — even in moderation. I think that it’s hard in that it might not be ideal circumstances to build muscle and have to wear a mask everywhere, but it’s all about maintenance and habits in the long run.

Other items on the differential:

Dr. Vinay Prasad gave this speech about how to critically appraise oncology trials, and I thought it was a good watch. I really enjoyed him talking about the multiple testing errors which nutritional epidemiologists pursue in finding statistical significance, and the various disadvantages of using surrogate endpoints to approve cancer medications. I think I’m going to use a lot of these techniques to analyze cancer / drug trials moving forward.

This piece by Ben White about the perils of very early cancer screenings through whole-body scans with companies like PreNuvo was very interesting. Finding incidental-omas, imperfections of your body which may not progress to full-blown cancer, is a fool’s errand according to him. I’m still convinced that the risk/benefit on an individual level is still justified, especially if the patient is taking that cost on. I think the more data that patients have to make a decision, the more informed they can be. Whether they use that to their advantage is up to them. In this vein, Neko Health raised $260M to bring their technologies to the US. So VCs are definitely betting that Daniel Ek can expand this ultra-preventative testing to US markets.

I don’t have access to a scale, so no graph this week unfortunately. Not the best way to show my change in weight, but hey, I don’t have access to one. I’ll update it next week when I’m back.

THE WEEKLY DOSE

Indians are weak — or are they?

As I’m in India, I’m doing as the Indians do. As a person of Indian descent, I think that there are things that I’m very optimistic about in India — the vibe shift that I’ve felt versus being in the United States is one of unbridled energy and the recognizance that the Indian economy is one of the fastest developing, most entrepreneurial places in all of Asia. On the other hand, there remain health issues which need to be solved — more specifically, the alarmingly high rates of chronic diseases such as obesity, type II diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

In my week in India, I’ve sampled a traditional Indian diet (albeit modified much to the chagrin of my relatives who try to heap on more of the food and exhort me to take more) and observed the lifestyle in two major Indian cities. I’ve realized a few things:

Most of the diet is made up of carbohydrates. Traditional dishes like kichidi, methi parathas, chole bhature, bhajis, rotis lack a key macronutrient — protein. People repeat the oft-repeated myth that “dal” or lentils contain all the protein that you need. I think this is a mistake — even with a vegetarian diet, if you’re trying to build muscle and ward off metabolic disease, you need to supplement protein in order to get a stable energy balance day-to-day.

It’s hard to have a conversation around how much macronutrient dietary requirements people need without recognizing that South Asians are at a high propensity for lifestyle-specfic diseases. While I’m really excited to see India developing so much, it’s a risk which is only going to compound seeing how many people are in the subcontinent. This is only compounded by the fact that the diet contains a bunch of sugar — it’s in the chai, it’s in the yogurt, and in all of tasty sweets that Indian people eat.

There is a large rift between working-class Indians and white-collar Indians in terms of the diet / lifestyle that they practice. Working-class Indian people are still more likely to exercise in their day-to-day work, but as India develops, it is starting to develop an accentuated phenotype of someone who is sedentary due to the lack of exercise. Due to the proclivity of people of Indian descent to develop chronic lifestyle diseases, it becomes very easy for the people who transitioned in one generation to develop those same diseases if they don’t make a conscious effort to exercise.

With that, I was curious to know how South Asians rank against other races when it comes to warding off the “four horsemen” of chronic disease, and I found an investigation by Alkhayl et al. where they investigated different muscle protein synthesis markers and responses to training in South Asian versus White European men.1

Deciding if South Asians reap lesser rewards from resistance training

In this investigation, 18 healthy participants of South Asian descent (from India, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, or Sri Lanka) and 16 healthy participants of white European descent from the Glasgow area were selected to evaluate how their muscle protein synthesis differed after a bout of resistance exercise training program over 12-week resistance program with 2 training sessions per week. They measured their metabolic rate, body composition, torque development, VO2 max, and a mixed-meal tolerance test before they started the program. The workouts in the program consisted of a 1-set of leg press, bench press, leg extension, shoulder press, leg flexion, seated row, calf raise, latissimus pulldown and biceps curl. The 1RM was re-tested at weeks 4/8 and it was adjusted accordingly.

The authors mention that while they were able to analyze a minimally clinical difference in the two groups, these conclusions are strictly exploratory work and that they need more time to see if these effects are replicable.

Muscle protein synthesis does not differ between two groups, but there remain important differences

The investigators ran a whole lot of linear regressions on this data and found some significant associations. Before we dive into the results — I’m generally not a fan of these multiple testing papers, even if they are hypothesis finding and observation generating, because you can become very tied into the magic value of p < 0.05 for statistical significance to draw conclusions, when the real alpha you should be measuring to avoid type I errors should be a lot lower owing to the Bonferroni correction.

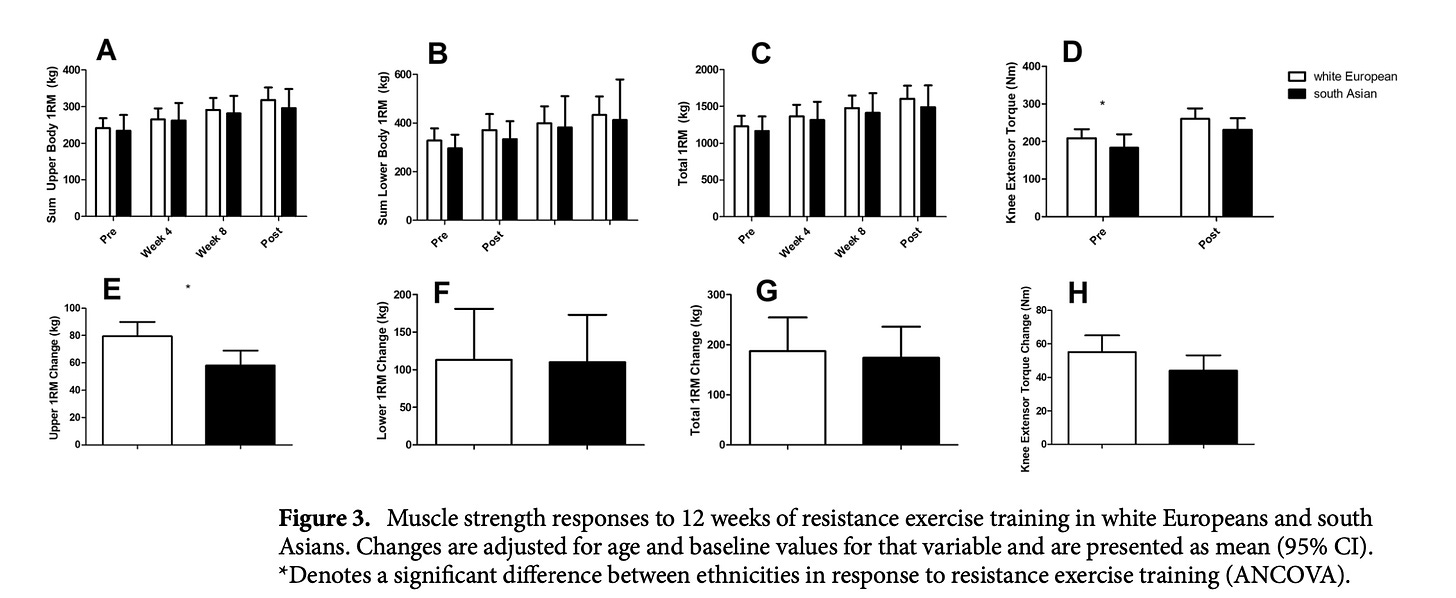

First, south Asians had less of an increase in 1RM (Figure 3E, p=0.015) versus white Europeans. A priori, I would have told you the same thing based on anecdotes, but good to have a study confirming it.

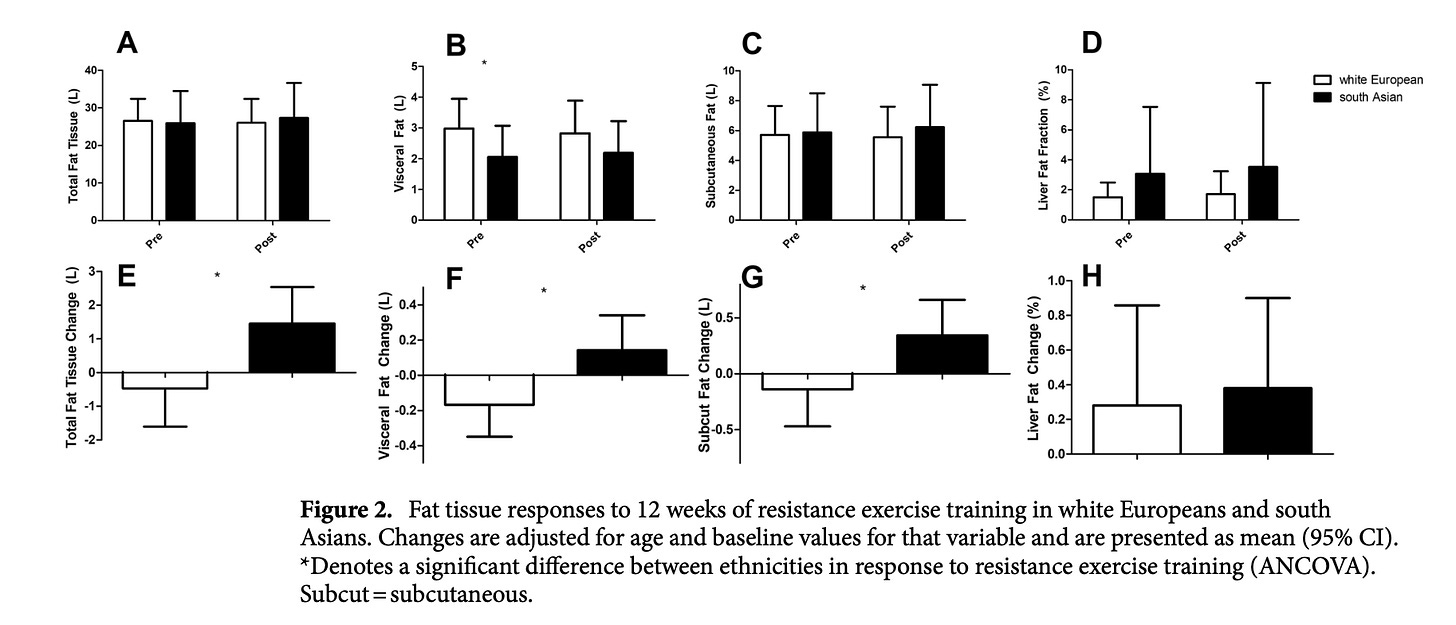

Moving onto other significant results, post-resistance training South Asians actually had an increase in total (Figure 2E, p=0.008), visceral (Figure 2F, p=0.029), and subcutaneous (Figure 2G, p=0.049) fat while Europeans had a decline in fat.

Even further, during baseline measurements, South Asians had a decreased VO2 max and this effect was seen even after resistance exercise training (p=0.008, Table 2). I’m not sure if they even completed any cardio training, so this seems off to measure as a metric to decide whether it can help muscle protein synthesis but I guess it was there and it was measured, so it offers some data point about VO2 max measurements in young south Asian males. I think what was also surprising was that the ages of the groups were also significantly different, with the south Asian group actually younger than the white European males (24 vs 29).

This makes me depressed — what to do about it

This exploratory study says that South Asian males tend to gain muscle and strength at a lower rate then their white European counterparts, but don’t have significantly different muscle protein synthesis (MPS) rates. This is disheartening to say the least, partly because I am focused on building muscle. However, one of the things that makes me more determined to reach this goal is the fact that the timescale is so long. Practically, even if I am not oxidize fat or carbohydrates that well, I’m still going to be able to go to the gym at least 5x a week and focus on getting that weight up.

Most of the non-healthy people who live to their 100s are there due to their genes. It’s easy to get to a 100 and smoke and drink if your genes are protecting you. However, this paper and my experiences in India make it clear that south Asians have the cards stacked against them. It’s hard to follow a good diet and exercise pattern, and you’re probably not going to help your chances from eventually developing diabetes if you’re lazing around all day and not actually moving your body. Therefore, as a south Asian, I’ve learned I have to take both the resistance training and my diet / sleep very seriously if I’m trying to emulate the same phenotype as people descended from other continents.

One of the surprising findings was that the total and visceral fat increased. I’m not sure what to make of that, although the authors mentioned that there was no change in insulin sensitivity over the 12-weeks of resistance training for south Asians. Chalk it up to our propensity for type II diabetes.

While this is very depressing, I think there’s a couple of takeaways I am going to work on for next week:

The cards that you are dealt are not the outcome of the game. I’m going to take this paper in stride and focus on how I can create the best hypertrophy program that I can muster to keep moving onwards

Focus on what you can control. I can control going into the gym and lifting heavy weights. Can’t really control if my genes have plans for me that I have yet to know about, but I can lift some heavy-a** weights.

REMEMBER, IT’S JUST COMMON SENSE.

Thanks so much for reading! Let me know what you thought by replying to this email.

See you next week,

Shree (@shree_nadkarni)

The information provided here is not medical advice. This does not constitute a doctor patient relationship and this content is intended for entertainment, informational, and educational purposes only. Always consult with a doctor before starting new supplementation protocols.

Alkhayl, Faris F. Aba, et al. “Muscle Protein Synthesis and Muscle/Metabolic Responses to Resistance Exercise Training in South Asian and White European Men.” Scientific Reports, vol. 12, no. 1, Feb. 2022, p. 2469. www.nature.com, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-06446-7.